GCNF is pleased to announce the launch of the third round of data collection for the Global Survey of School Meal Programs.

Continue readingStatus of the School Canteen in Burundi

Status of the School Canteen in Burundi

This is a guest blog written by Mr. Liboire BIGIRIMANA, National Director of School Canteens in Burundi and Spokesperson for the Ministry of National Education and Scientific Research and Focal Point for Burundi, 2021 Global Survey of School Meal Programs

School canteens in Burundi have been in existence since the 1960s supported by the interventions of the World Food Programme (WFP). WFP supplied schools having boarding facilities with commodities such as powdered milk, meat, and canned fish. In 2008, the northern provinces of Burundi were affected by climate change, in the form of drought, leading to the impoverishment of households. This situation forced children to drop out of school and flee to neighboring countries of Burundi, mainly Tanzania and Rwanda. Others have moved to major cities in Burundi in order to get jobs and earn money.

To remedy this situation, the WFP and the Government of Burundi entered into an agreement to finance hot midday meals to motivate children to return to school for classes.

In 2013, the philosophy of the school canteen changed from being an emergency response to a development intervention. In this new approach, the Government of Burundi decided to develop an endogenous school canteen system known as Home Grown School Feeding, whereby a school canteen obtains local products from small producers grouped into cooperatives and agricultural production associations, thus forming a permanent market with the small producers.

I. Major Achievements of the Government in School Feeding

Several major achievements have been made by the Government of Burundi including:

Institutional aspects

- In 2016, a National Directorate of School Canteens was created and housed institutionally at the Minister’s Cabinet;

- On 14th November 2018, the Government of Burundi validated and endorsed the National School Feeding Program (NSFP), a tool for strategic orientation and dialogue with Development Partners (PTF);

- In 2020, Her Excellency the First Lady of Burundi Mrs. Angéline NDAYISHIMIYE agreed to be the Patron of the National School Feeding Program;

- In 2021, Burundi joined the Global School Meals Coalition.

Regarding financial commitments, since 2008 the Government of Burundi has made its counterpart funds available to WFP to finance the purchase of commodities for the school canteen. The amount allocated to school feeding by the government is about 2 million US dollars. Government contribution is expected to reach 6 million US dollars by the start of the 2023-2024 school year!

A study carried out locally shows that the school canteen contributes to the improvement of school indicators and the standard of living of producers.

II. Geographical Coverage

The National School Feeding Program (NSFP) intervenes in 847 elementary schools across 7 provinces of the country namely Bubanza, Bujumbura, Cibitoke, Gitega, Muyinga, Ngozi, and Kirundo provinces. About 650,000 school children out of an estimated target of 2.8 million children in elementary schools benefit from the NSFP. To achieve universal school canteen coverage, a substantial mobilization of funds needs to be done by development partners, the government, and the communities to fill current coverage gaps.

III. Best Practices in School Feeding in Burundi

The implementation of the NSFP faces several challenges, due to, most notably, limited financial resources. In addition, innovations are needed at the canteen level, especially related to the use of firewood and environmental degradation. The school feeding implementers in Burundi are developing best practices, including the following:

a) To limit the volume of firewood to be used, schools considered building improved stoves (i.e. utilizing concrete stoves that use less firewood and conserve heat thereby drastically reducing the quantity of carbon dioxide released into the atmosphere), and the use of “briquettes”, fuel obtained following the industrial compaction of household residues, grasses, and rice crop residues

b) For good governance of the school canteen, a stock management tool has been introduced in schools with school canteens known as “School Connect”. This approach utilizes a digital management tool installed on tablets which allows for efficient and effective tracking and management of inventory. The tool provides an idea of the actual use of food in relation to the number of beneficiaries;

c) The consumption of products with very high nutritional value such as mushrooms and milk for a consistent protein intake;

d) The involvement of communities to support the school canteen: communities participate in the preparation and distribution of school meals, provide firewood, water, and vegetables to supplement the children’s food ration;

e) The introduction of decentralized purchases: the Government of Burundi and the WFP provide those in charge of the decentralized structures with the financial means to buy commodities for the canteen directly from food producers. This approach is helps canteens overcome stock-outs, increases the quantities of accessible commodities, and cuts down on the exorbitant cost of transporting food;

f) Introduction of hydroponics, a means of producing vegetables in greenhouses in areas with water deficits to supplement school meals with vegetables.

IV. National School Feeding Program Partners

The implementation of the NSFP is supported by the interventions of various development partners, including the World Bank (construction of improved stoves and their shelters, the supply of funds to buy commodities), the Netherlands, the Global Fund for Education through the French Development Agency (AFD), the Russian Federation, The Rockefeller Foundation (Financial and technical support), the United States of America through the McGovern-Dole Food For Education program. At the local level, the development of the fortified milk and corn flour value chain rose out of local partnership. Successful partner contributions are characterized by success in increased environmental protection, supplying of healthy, rich, and nutritious meals, ensuring the good governance of the school canteen, and more.

V. Participation of Burundi in Global Child Nutrition Forums

Since 2014, Burundi has participated in most of the Global Child Nutrition Forums, organized by the Global Child Nutrition Foundation (GCNF). Burundi has participated in Forums organized in Brazil, Cape Verde, South Africa, Canada, Tunisia, Armenia, and Benin. All these Forums have enabled Burundi to capitalize on the experiences of other countries in the management, financing, and sustainability of school feeding. For example, the Forum held in Brazil helped Burundi draft its school feeding policy. At the Forum held in Montreal, Canada, Burundi was able to build partnerships to finance the school canteens. At the Benin Forum in 2022, Burundi was able to better understand the part each government played in financing its school feeding. This is why, as of September 2023, Burundi will finance school feeding to the tune of 12.7 billion Burundian Francs, i.e. 6 million US dollars, an increase of 164% compared to the financing of previous years (4.8 billion Burundian Francs)!

Situation de la Cantine Scolaire Au Burundi

Situation de la Cantine Scolaire au Burundi

Écrit par M. Liboire BIGIRIMANA, le Directeur National Des Cantines Scolaires au Burundi et Porte Parole du Ministre de l’Education Nationale et de la Recherche Scientifique et Point Focal, Enquête Mondiale du GCNF sur L’Alimentation Scolaire 2021

La cantine scolaire au Burundi a vu le jour depuis les années 1960 avec les interventions du PAM sous forme de fourniture aux Ecoles à régime d’internat des commodités essentiellement composées par du lait en poudre, de la viande et du poisson en boîte de conserve. En 2008, les provinces du Nord du Burundi ont été affectées par des changements climatiques, sous forme de sécheresse, ayant abouti à la paupérisation des ménages, une situation qui a contraint les enfants à abandonner l’école et ont fui vers les pays limitrophes du Burundi : la Tanzanie et le Rwanda. Les autres ont regagné les grandes capitales du Burundi dans le souci de se faire embaucher et gagner de l’argent.

Pour pallier à cette situation, le PAM et le Gouvernement du Burundi ont convenu à travers un Accord, de financer des repas chauds de midi, pour motiver les enfants à regagner les salles de cours.

En 2013, la philosophie de la cantine scolaire est passé du concept d’intervention d’urgence en intervention de développement dans le sens où le Gouvernement a décidé que soit développé une cantine scolaire qui s’approvisionne en produits locaux, pour constituer un marché permanent des petits producteurs regroupés dans des coopératives et Association de production agricole, d’où le concept d’une cantine scolaire endogène (Home Grown School Feeding).

I. LES GRANDES REALISATION DU GOUVERNEMENT EN MATIERE D’ALIMENTATION SCOLAIRE

- En 2016, il a été créé une Direction Nationale des Cantines Scolaires ayant pour encrage institutionnel au niveau du Cabinet du Ministre,

- Le 14/11/2018, le Gouvernement du Burundi a validé et endossé le Programme National d’Alimentation Scolaire, un outil d’orientation stratégique et de dialogue avec les Partenaires au Développement (PTF) ;

- En 2020, SE la Première Dame du Burundi Madame Angéline NDAYISHIMIYE a accepté d’être Marraine du Programme National d’Alimentation Scolaire ;

- En 2021, le Burundi a adhéré au sein de la coalition Mondiale des Repas Scolaires.

Au niveau engament financier : le Gouvernement du Burundi a depuis 2008, mis à la disposition du PAM sa contrepartie pour financer l’achat des commodités en faveur de la cantine scolaire. Les montants alloués par le Gouvernement à l’alimentation scolaire sont de l’ordre de 2 millions de dollars us. Ces contributions du Gouvernement devraient atteindre 6 millions de dollars us avec la rentrée scolaire 2023-2024!

Une étude réalisée localement montre que la cantine scolaire contribue à l’amélioration des indicateurs scolaires et le niveau de vie des producteurs.

II. LA COUVERTURE GEOGRAPHIQUE

Le Programme National d’Alimentation Scolaire (PNAS) intervient en faveur de 847 Ecoles Fondamentales à travers 7 provinces du Pays (Bubanza, Bujumbura, Cibitoke, Gitega, Muyinga, Ngozi et Kirundo). Le Total des bénéficiaires du PNAS s’élève à plus de 650.000 écoliers sur une cible estimée à 2,8 millions d’enfants de l’Ecole Fondamentales. Pour réussir une cantine universelle, une mobilisation conséquente des fonds devrait se faire et par les PTFs, le Gouvernement et les communautés pour combler les gaps.

III. LES MEILLEURS PRATIQUES EN MATIERE D’ALIMENTATION SCOLAIRE AU BURUNDI

La mise en œuvre du PNAS se heurte à plusieurs défis liés notamment aux ressources financières assez limitées pour répondre à une demande de terrain de plus en plus croissante. En outre, une cantine innovante est un impératif suite à la nécessité de protéger l’environnement dans un contexte où la principale source d’énergie pour préparer les repas des enfants reste le bois de chauffe. L’idée est d’asseoir des mécanismes innovants pour éviter que la cantine scolaire ne soit pas la cause de dégradation de l’environnement. Les meilleurs pratiques sont notamment :

a) Pour limiter le volume de bois de chauffe à utiliser, nous avons pensé à la construction des foyers améliorés institutionnels (foyers en béton utilisant peu de bois de chauffe et conservant la chaleur et réduisant drastiquement la quantité de dioxyde de carbone rejetée dans l’atmosphère) et l’utilisation des briquettes (combustibles obtenus suite au compactage industriels des restes ménages, des herbes et des restes des récoltes du riz).

b) Pour une bonne gouvernance de la cantine scolaire, un outil de gestion des stocks a été introduit dans les écoles à cantine scolaire : School connect. Il s’agit d’une gestion digitalisée qui se fait sur des tablettes et qui permet de faire un track efficient et efficace de la gestion des stocks. L’outil permet d’avoir une idée sur l’utilisation des vivres en tant réel par rapport au nombre de bénéficiaires;

c) La consommation des produits à très haute valeur nutritive comme les champignons et le lait pour un apport protéinique consistant,

d) L’implication des communautés pour appuyer la cantine scolaire : les communautés participent à la préparation et distribution des repas scolaires, apportent du bois de chauffe, de l’eau et des légumes pour compléter la ration alimentaire des enfants ;

e) L’introduction des achats décentralisés : le Gouvernement et le PAM mettent à la disposition des responsables des structures déconcentrées des moyens financiers pour acheter au près des producteurs les commodités en faveur de la cantine. Cette approche est l’un des éléments pour pallier aux ruptures de stocks et augmente les quantités des commodités car est une solution aux coûts exorbitants du transport des vivres ;

f) Introduction de l’hydroponie (production des légumes sous serre dans les zones à déficits hydriques pour compléter les repas scolaires en légumes.

IV. LES PARTENAIRES DU PROGRAMME NATIONAL D’ALIMENTATION SCOLAIRE

La mise en œuvre du PNAS est appuyée par les interventions des différents partenaires au Développement. Ces partenaires sont essentiellement la Banque Mondiale (construction des foyers améliorés et leurs abris, la fourniture des fonds pour acheter des commodités), les Pays Bas, le Fonds mondial pour l’Education à travers l’Agence Française de Développement(AFD),la Fédération de Russie, La Fondation Rock Feler (Appui financier et technique), les USA à travers McGovern-Dole. Au niveau local, le partenariat se traduit par le développement de la chaîne de valeur lait et farine de maïs fortifiée…..Les progrès réalisés grâce au partenariat se traduit par leur contribution à la protection de l’environnement, la fourniture des repas sains riches et nutritifs, assurer la bonne gouvernance de la cantine scolaire…

V. PARTICIPATION DU BURUNDI AUX FORUMS GCNF

Depuis 2014, le Burundi a participé à la plus part des forum organisés par le GCNF. Le Burundi a participé notament aux Forum GCNF organisés au Brésil, Cape Verde, Afrique du Sud, Canada, Tunisie, Arménie et au Bénin. Tous ces Fora ont permis au Burundi de capitaliser les expériences des autres pays en matière de gestion, de financement et pérennisation de l’alimentation scolaire. Pour exemple, le forum GCNF du Brésil a permis au Burundi de rédiger sa politique d’alimentation scolaire. Pour le forum GCNF de Montréal au Canada, il a permis au Burundi de bâtir des partenariats pour assurer le financement de la cantine scolaire. Pour le forum GCNF du Bénin, le Burundi a pu comprendre la part du chaque Gouvernement à financer lui-même l’alimentation scolaire. C’est pourquoi, dès septembre 2023, le Burundi financera l’alimentation scolaire à hauteur de 12,7 milliards de Francs Burundais soit 6 millions de dollars US, soit une augmentation de 164% par rapport aux financements des années précédentes (4,8 milliards de Francs Burundais)!

On notera des visites d’échange d’expériences régulièrement organisées et auxquelles a participé SE la Première Dame et Marraine du Programme d’Alimentation Scolaire au Burundi Madame Angéline NDAYISHIMIYE. Il s’agit des visites d’échange d’expérience faites au Bénin en 2021 et au Sénégal en 2023.

Food Systems, Climate Change, and School Meals

With the UN Food Systems Summit +2 Stocktaking Moment happening this week, GCNF wanted to take a closer look at the relationship between food systems, the climate, and school feeding programs.

Continue readingCantines Scolaires : L’Experience de l’Alimentation Scolarie Basée Sur la Production Locale (ASPL), Booste le Dynamisme des Cantines Scolaires au Togo

Depuis 2020, les cantines scolaires au Togo ont pris une nouvelle allure en migrant de la sphère de projets vers un véritable programme national d’alimentation scolaire.

Continue readingSchool Canteens: The Experience of Home-Grown School Feeding (HGSF) Boosts the Dynamism of School Canteens in Togo

Since 2020, school canteens in Togo have taken on a new look by migrating from the sphere of projects towards a truly national school feeding program.

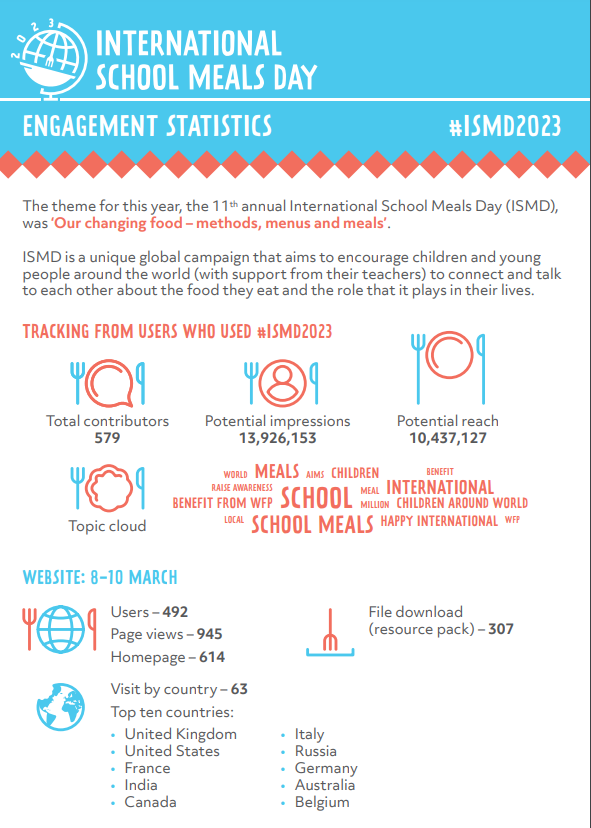

Continue readingEleven Years of International School Meals Day

Eleven Years of International School Meals Day

Children in Scotland manages International School Meals Day (ISMD) and in this guest blog, Head of Engagement & Learning, Simon Massey reflects on how the initiative has developed over the years.

I started working at Children in Scotland in 2015 and ISMD was already well-established as a partnership between Scotland and the US, with a wide range of organisations across the world, including the Global Child Nutrition Foundation, working hard to support the day. From the beginning the aim was to create a unique campaign that raised awareness of good nutrition for all children, and, thanks to ongoing Scottish Government funding, that continues today.

The initiative has changed and developed over the years but has held onto some core elements including:

Raising awareness of the importance of the nutritional quality of school meal programs worldwide

Promoting the connection between healthy eating, education, and better learning

Connecting children around the world to foster healthy eating habits and promote wellbeing in schools

Sharing success stories of school meal programs around the globe.

ISMD2023, which took place on 9 March 2023, was once again a success. This year’s theme was ‘Our changing food – methods, menus and meals’.

We saw an increase in the number of countries getting involved, from 47 in 2022 to 63 this year, while our potential online reach jumped from 3.3 million in 2022 to an amazing 10.4 million this year! Numbers downloading our online resources almost tripled in the past year and we had 579 different individuals or organisations contribute one way or another this year.

The ISMD website and Twitter provide a one-stop shop for people to explore the things that have been shared over the past few years. The website also has resources and activities that can be used in schools. Each year we try to do something new – the past two years, for example, have included an online ‘quilt’ that pulls together a wide range of images from each year’s ‘shared practice’, and this year for the first time, we produced a series of ‘Top 10’ activity sheets, encouraging children and young people to consider their local food, healthy options and favourite school meals.

Although ISMD2023 was only a few weeks ago, we’re already starting to think about what we’ll do for next year. There will still be a range of resources developed and we will come up with a new theme for the day, but we’re also really interested in developing an ISMD Commitment Mark… watch this space!

If any of this inspires you to get involved, or you have any ideas for next year, please get in touch at ismd@childreninscotland.org.uk – we want to keep building on all our successes and continue to spread the word.

About the Author

Simon Massey | Head of Engagement & Learning

Simon is part of Children in Scotland’s Leadership Team and manages the Engagement & Learning Department, comprising the Communications & Marketing team, Learning & Events team and the Membership Service. He also coordinates Children in Scotland’s child protection activity.

He has a keen interest in equality and diversity, particularly LGBT+ issues and led the organisation through LGBT Youth Scotland’s LGBT Charter of Rights accreditation in 2018-19. He is also a member of the Social Work Cross-Party Group and SCVO’s Intermediaries Network.

Simon joined Children in Scotland in September 2015 and has 35 years’ experience working in the children’s sector in various roles including volunteer, front-line practitioner, manager and consultant.

He is a qualified social worker and has undertaken extensive child protection and post-abuse therapeutic social work as well as work in residential childcare settings. He is also a qualified practice teacher with experience of the social work education field and local authority workforce development.

Outside of Children in Scotland, Simon is the Chair of Bright Light, an Edinburgh-based charity providing relationship counselling services and he spends a large amount of time chasing his dog, Alfie, around

How 5 GPE Partner Countries are Helping Students Attend Schools

Read how GPE is supporting Burundi, the Federated States of Micronesia, Nicaragua, Somalia, and Yemen to ensure students can learn in good conditions through school feeding programs.

Continue readingFebruary Newsletter

AgriPulse Opinion: Global school feeding programs

By Marshall Matz and Julia Johnson, OFW Law

International school feeding programs have long been recognized as an important investment in a child’s nutrition and health outcomes. Recently, the Global Child Nutrition Foundation (GNCF) set out to fill the need of documenting school feeding programs consistently and comprehensively through issuing the first of its kind Global Survey of School Meal Programs. They have just published findings from the survey in the new report “School Meals Around the World”, which provide necessary insight into the power of school meals in shaping the food and education system. The GCNF brings together governments, civil society, and the private sector to expand opportunities for children to receive adequate nutrition for learning and achieving their potential.

Teachers know all too well that hungry children do not learn effectively and that school meal programs are critical to satisfying this need. Beyond fulfilling daily health and nutrition needs, school meal programs incentivize regular school attendance, keep kids – particularly girls – in school for longer, promote literacy, and support agricultural supply chains, among other advantages. Further, educating girls means that they get married later, have fewer children, and are upwardly mobile.

The GCNF report found that nearly three-quarters of the programs served as a social safety net for families who could not afford to feed their children. A smaller percentage of programs aimed to meet agriculture goals or obesity prevention and mitigation outcomes. Dietary diversity increased when food was purchased closer to where the school meal program was located, with 82 percent of programs purchasing some or all school food in-country and 72 percent purchasing locally. In some instances, farmers were directly engaged in school meal operations. Programs can also play a significant role in women’s economic empowerment, with 67 percent of programs reporting a focus on creating jobs or leadership opportunities for women.

Notably, the report finds that school meals have the potential to transform local food systems. Not only do they drive agricultural economic growth, but they also help shift food systems towards targeting the needs of children. Furthermore, schools serve as a food environment where healthy diets can be instilled. These findings are very timely given the upcoming U.N. Food Systems Summit (FSS) in September 2021.

Input into the FSS is being guided by five action tracks, each charged with finding game-changing solutions to the world’s greatest food system challenges. In an interview conducted by GCNF Executive Director Arlene Mitchell on the report, Dr. Lawrence Haddad, Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition Executive Director and FSS action track 1 chair, said that school feeding has often been featured in the solutions space for the FSS. He says, “The education system and the food system are intricately linked, and they can be made more intricately linked in a positive way.”

Given the advantages of school meals, the 2002 Farm Bill authorized the McGovern-Dole Food for Education program. The program, implemented by the Department of Agriculture (USDA), delivers U.S. agricultural commodities and financial and technical assistance to food-insecure countries to establish school feeding programs. According to the most recent USDA report, McGovern-Dole is currently reaching over 4.1 million people through 46 active projects in 30 countries.

GCNF also issued a special report on school meal programs in the 41 countries that received McGovern-Dole food assistance between 2013 and 2018 and/or were eligible to receive support in the 2018-2019 fiscal year. From the McGovern-Dole report findings, GCNF developed a series of recommendations for the U.S. government and implementing partners to increase program sustainability and therefore, as Dr. Haddad puts it, tie the food and education system together in a more meaningful way. These recommendations include increasing national government engagement, supporting fortified food supply chain development, increased monitoring and evaluation around gender, and formalizing job opportunities that support McGovern-Dole implementation.

COVID-19 has disrupted school meal programs, helping to drive unprecedented levels of hunger in modern history. According to the World Food Programme (WFP), 370 million children have missed school meals due to COVID-19 related closures. Today, WFP estimates that 73 million primary school-aged children need school meals. Despite challenges, many schools have been able to pivot their programming by, for example, providing take-home rations. The reports from GCNF are a critical tool for those in the school feeding community and beyond to share knowledge, identify trends, strengths, and weaknesses in school feeding, and advocate for school meal programs, especially as a pathway to recovery and sustainable economic growth.

The GCNF is conducting their 2021 Global Survey of School Meal Programs which will aim to capture the full impact of COVID-19 of the pandemic for at least one full school year. For more information, please visit www.gcnf.org.

Marshall Matz specializes in global food security at OFW Law in Washington, D.C. mmatz@ofwlaw.com Julia Johnson is an Agricultural Legislative Assistant at OFW Law. jjohnson@ofwlaw.com