Today, as environmental challenges grow, there is much we can learn by looking back and rediscovering how to live as they did. This desire to reconnect with ancestral wisdom inspired me to set up the “Mwinimunda Heritage Homestead Project” in Lusaka, Zambia.

Continue readingRelearning to Live Like My Great-Great-Grandmother: Embracing Heritage Climate-Smart Crops for Health and the Environment

Today, as environmental challenges grow, there is much we can learn by looking back and rediscovering how to live as they did. This desire to reconnect with ancestral wisdom inspired me to set up the “Mwinimunda Heritage Homestead Project” in Lusaka, Zambia.

Continue readingA Window of Opportunity Not to be Missed: Investing in Adolescent Girls

Adolescent girls and young women stand to gain the most from a stronger focus on the first 8,000 days of life. However, in many cultures around the world, women and girls often eat last and eat least, affecting both their short and long-term health.

Continue readingGCNF Newsletter for September 2024

The Global Child Nutrition Foundation (GCNF) invites you to attend the Global Child Nutrition Forum taking place in Osaka, Japan from 9 through 12 December 2024! This four-day learning exchange is organized by GCNF and International Child Nutrition Japan in collaboration with the Government of Japan and the School Meals Coalition (SMC).

Continue readingBuilding the evidence: Early nutrition sets the stage; subsequent investment plays out across childhood

The first 1,000 days of a child’s life—from conception to their second birthday—are a critical period for nutrition. During this window, appropriate nourishment lays the foundation for physical growth and development, neuro-cognitive development, and overall health.

Continue readingShokuiku – How Japan Leverages School Meals as a ‘Living Textbook’ for Lifelong Healthy Eating

In Japan, school meals go beyond just a meal and serve as a “living textbook” to prepare children with the good judgment required for lifelong good nutrition and sustainable diets.

Continue readingThe 2024 Global Child Nutrition Forum – Why Japan?

The 2024 Global Child Nutrition Forum will beheld in Osaka, Japan in December 2024. Japan was selected as the location of the 24th edition of this event because it stands out for providing a nationally owned and managed high quality school meal program.

Continue readingGCNF Newsletter for June 2024

The Global Child Nutrition Foundation (GCNF) invites you to register to attend the Global Child Nutrition Forum happening in Osaka, Japan from December 9 through 12, 2024.

Continue readingGCNF Newsletter for April 2024

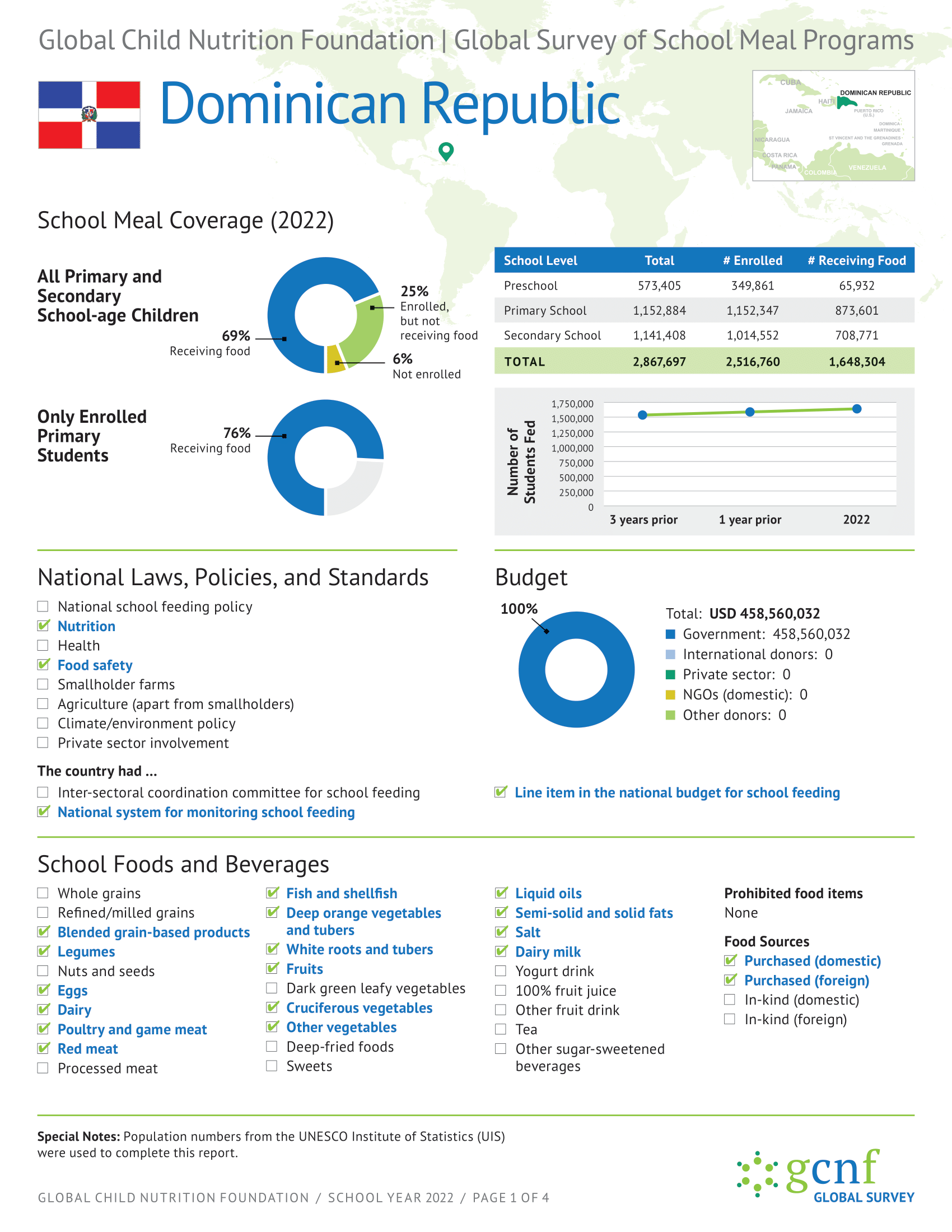

Governments from around the world are encouraged to participate in the 2024 Global Survey of School Meal Programs by completing the 2024 Global Survey Questionnaire.

Continue reading