Climate-Smart School Meal Programs

by Melissa Pradhan, Survey Associate: Asia, The Pacific, & The Middle East

The IPCC Reports have repeatedly called for alarms to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in order to limit the increase of global average temperature to 2ºC, if not 1.5ºC. World class evidence and studies have indicated that failing to meet this target will result in catastrophic events with the potential to cause adverse cascading impacts on human life and the economy.

Emissions sourced from the Agriculture, Forest and Other Land Use sector alone have been noted to be just under a quarter of the total anthropogenic GHG emissions making up to approximately 10–12 Gigatonne of CO2eq per year (Smith, 2014). Mitigating GHG emissions from this sector, therefore, has the potential to deliver large-scale emission reduction.

In the 2020 academic year, 330.3 million students received school meal programs globally (GCNF, 2022). In the United States alone, the National School Lunch Program (NSLP) reaches millions of children every day. Nutrition Standards for the US NSLP shapes a USD 14 billion market and food service directors are obligated to adhere to the recommended nutrition standards. However, it was found that the current menus are not aligned with the latest nutritional science, and in addition have huge impacts on the environment. Researchers found that the NSLP menus incorporate the most carbon-intensive foods compared to the diet recommendations from the EAT-Lancet Commission’s healthy reference diet (Poole, 2020).

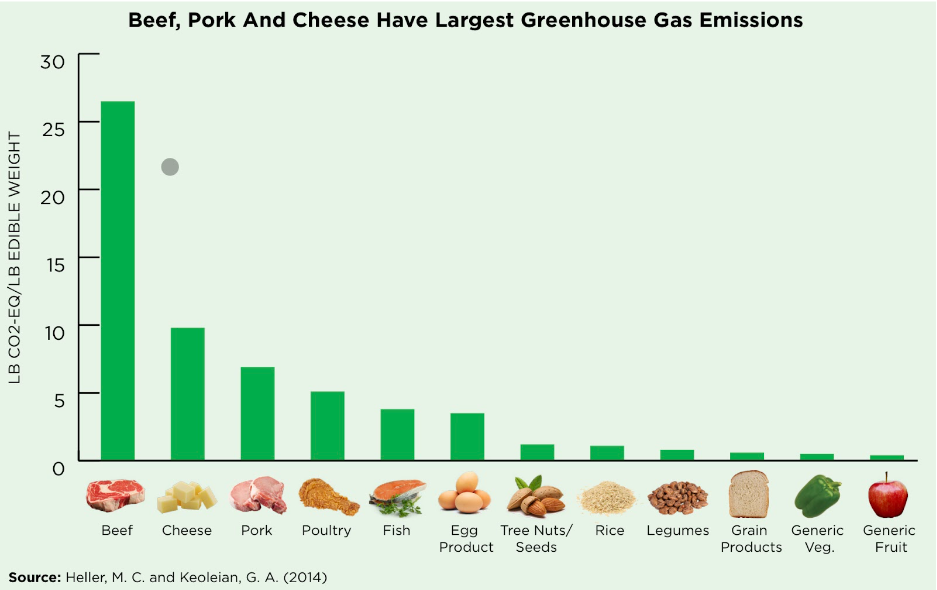

A study by Stern identified that the use of animal products in school lunches, mainly beef and dairy, was primarily the major driver of emissions (Stern, 2022). This is because beef hot dogs generate seven times more carbon than tofu and veggie stir-fry rice, for example. If all School districts opted for a reduced animal food menu, the US alone could minimize their carbon footprint by 700 million kg CO2eq that is equivalent to installing 99,000 residential solar panels or eliminating 150,000 cars from the roads for a year (Hamerschlag, 2017). In addition, reducing institutional purchase of factory-farmed meat can also strengthen local food systems.

Increasing evidence suggests that school meal programs can be made both healthier and climate-friendly at a low cost without having to compromise on meeting the recommended nutrition standards (Hamerschlag, 2017). As school districts have the liberty to design their own menu to meet the federal nutrition requirements, they hold the potential to influence dietary behaviors and the country’s agricultural landscape for years to come.

The Oakland Unified School District, for example, has already successfully implemented two initiatives – Oakland’s Lean and Green Wednesday Program, and California Thursdays through which they were able to successfully decrease their carbon footprint by 14% simply by reducing the frequency of meat, poultry and cheese in school lunches and opting for plant-based nutritious meals. The district also saved USD 42,000 by cutting costs by one percent per meal (Hamerschlag, 2017). In a similar manner, preliminary calculations suggest that the NSLP could also cut their cost from USD 3.81 per meal to nearly half if the EAT diet is incorporated into their menus.

Outside the United States, as a part of the National Climate Initiative, the German Federal Ministry for the Environment (BMU) has formed a joint project initiated and managed by the Institute for Future Studies and Technology Assessment (IZT) called Climate Efficient School Canteens (KEEKS). Through the project, 22 different ways to reduce GHGs have been analyzed and quantified through the “Measure-Map”. For example, the kitchen staff, chef and caterers are trained to prepare low-cost, healthy, sustainable meals, and utilize energy-saving appliances, plant-based ingredients and low-carbon meat alternatives. This way, KEEKS has significantly contributed to meet the German Government’s target of reducing 40% of the country’s GHG emissions by 2020 by training over 12,500 kitchen staff, reaching 23,000 students across Germany, and offering 140,000 students plant-based school lunches for a week.

Overall, to make school lunches more climate-friendly, some low-hanging fruits could be:

- Incorporating lunches that include more whole grains, seafood, nuts and seeds to meet the protein requirements.

- Reducing the frequency of serving beef and dairy and instead utilizing cheaper forms of protein such as legumes

- Switching to plant-centric meals and/or seafood

- Opting for energy-efficient kitchen appliances and behavior

In addition, local governments and nonprofits can also assist schools in building capacity to begin serving more sustainable lunches. The current policy requirements for school meals should also be updated to allow a wider variety of available climate-smart grain options. As more agricultural products are increasingly susceptible to the changing climate, expanding the options of food items on school menus can also ensure that we are climate-resilient and increase food security.

The world food system is not only driving climate change but also aiding increasing levels of diet-related diseases. It is imperative that we take initiatives to adopt sustainable diets and reduce carbon emissions wherever possible in order to safeguard human life. There are opportunities to opt for a lower carbon footprint for school meal programs through minor changes in our choices of items on the school menu, and the co-benefits in the form of reduced costs and increased nutrients in climate-friendly school meals can help us develop healthier lunches.

References

Global Child Nutrition Foundation (2022). School Meal Programs Around the World: Results from the 2021 Global Survey of School Meal Programs ©. Accessed at link.

Hamerschlag, K. & Polk, U.K., (2017). Shrinking the Carbon and Water Footprint of School Food: A Recipe for Combating Climate Change. Friends of the Earth. Accessed at link.

Poole, M.K., Musicus, A.A. & Kenney, E.L. (2020). Alignment of US School Lunches with the EAT-Lancet Healthy Reference Diet’s Standards for Planetary Health. Health Affairs V.39 N.12. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.01102

Smith, P. et. al. (2014). Agriculture, Forestry and Other Land Use (AFOLU). In: Climate Change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA. Accessed at link.

Stern, A.L., Blackstone, N.T., Economos, C.D. et al. (2022). Less animal protein and more whole grain in US school lunches could greatly reduce environmental impacts. Nature: Commun Earth Environ 3, 138 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-022-00452-3

UNFCCC (2018). Climate-Efficient School Kitchens and Plant-Powered Pupils Germany. Accessed at link.