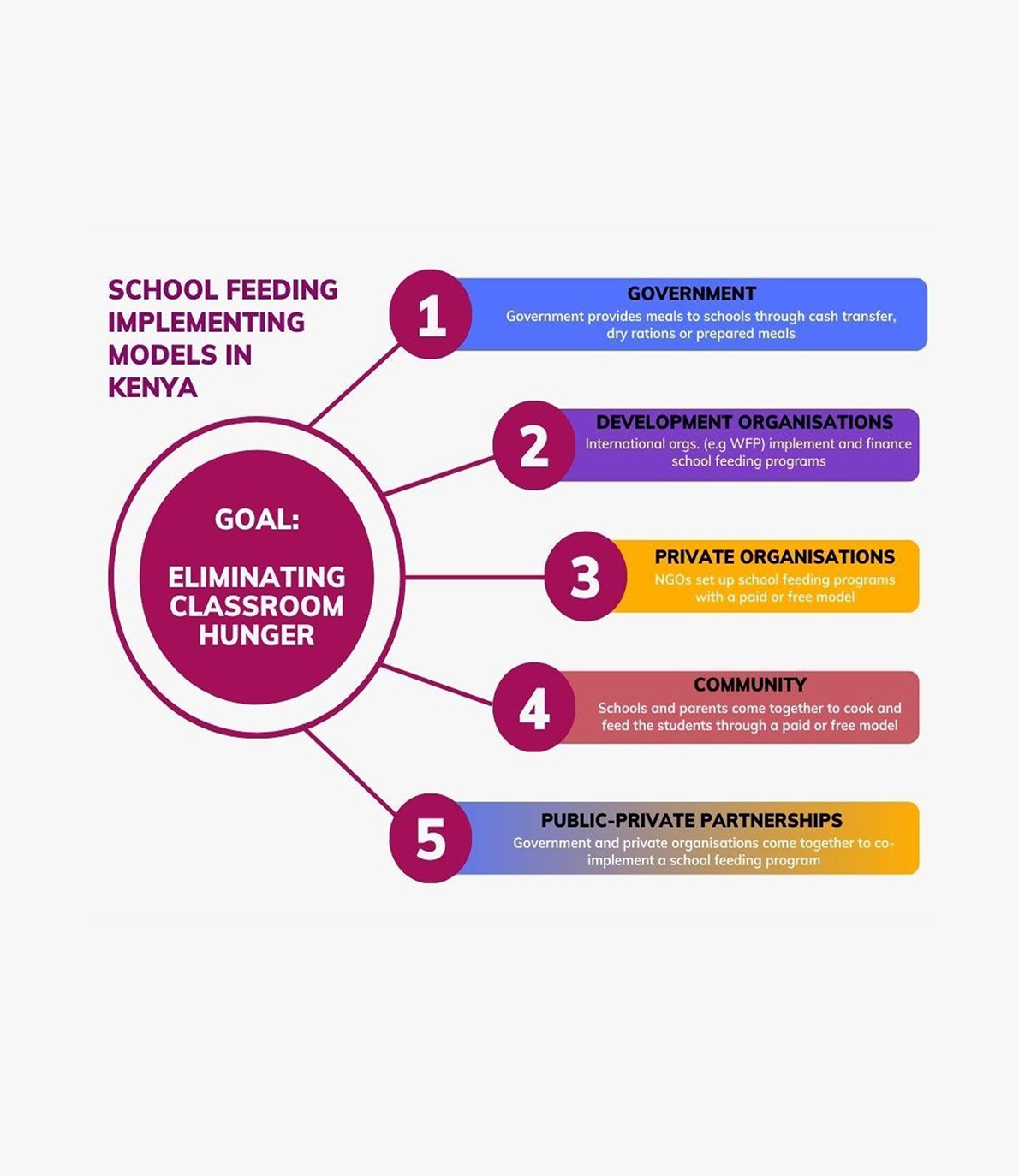

Each year on March 1st, the Africa Day of School Feeding highlights the transformative role of school meal programs in enhancing education, nutrition, and economic development across the continent. Established by the African Union in 2016, this year marks the 10th anniversary of the celebration, recognizing a decade of progress in using school meals as a powerful tool to improve student learning, boost school attendance, and support local food systems. By providing nutritious meals in schools, governments and communities across Africa help ensure that children have the energy and focus they need to thrive in the classroom and beyond.

Continue readingHighlights from the 24th edition of the Global Child Nutrition Forum

The 24

th edition of the Global Child Nutrition Forum – the world’s largest and longest

running Forum dedicated to supporting governments and their partners in implementing

high quality school meal programs – took place from 9-12 December in Osaka, Japan

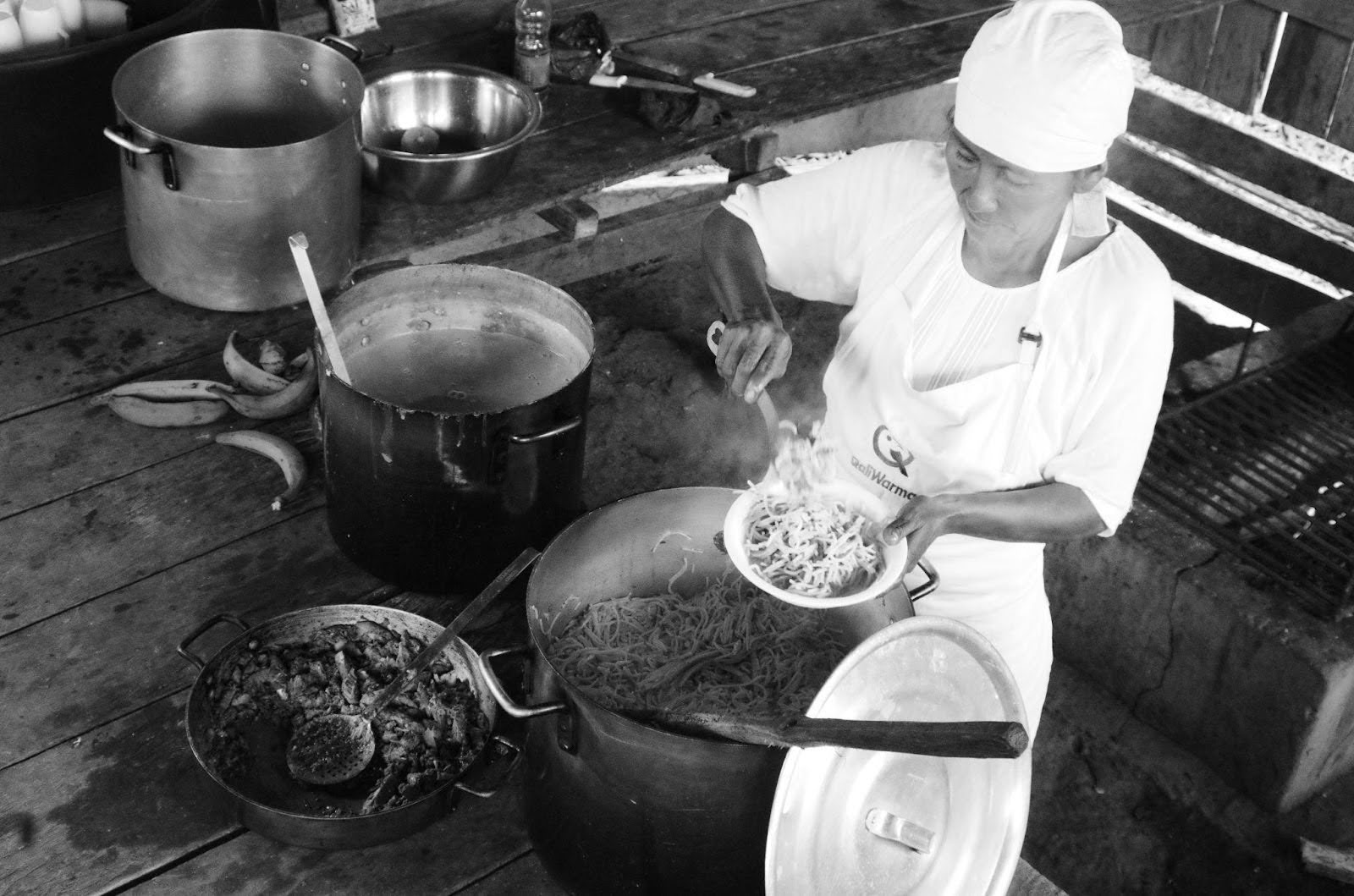

Seeing the Value of School Food Workers and Their Labor

K-12 School Nutrition Leaders Serve A Powerful Role In Growing Produce Consumption

Today, as environmental challenges grow, there is much we can learn by looking back and rediscovering how to live as they did. This desire to reconnect with ancestral wisdom inspired me to set up the “Mwinimunda Heritage Homestead Project” in Lusaka, Zambia.

Continue readingRelearning to Live Like My Great-Great-Grandmother: Embracing Heritage Climate-Smart Crops for Health and the Environment

Today, as environmental challenges grow, there is much we can learn by looking back and rediscovering how to live as they did. This desire to reconnect with ancestral wisdom inspired me to set up the “Mwinimunda Heritage Homestead Project” in Lusaka, Zambia.

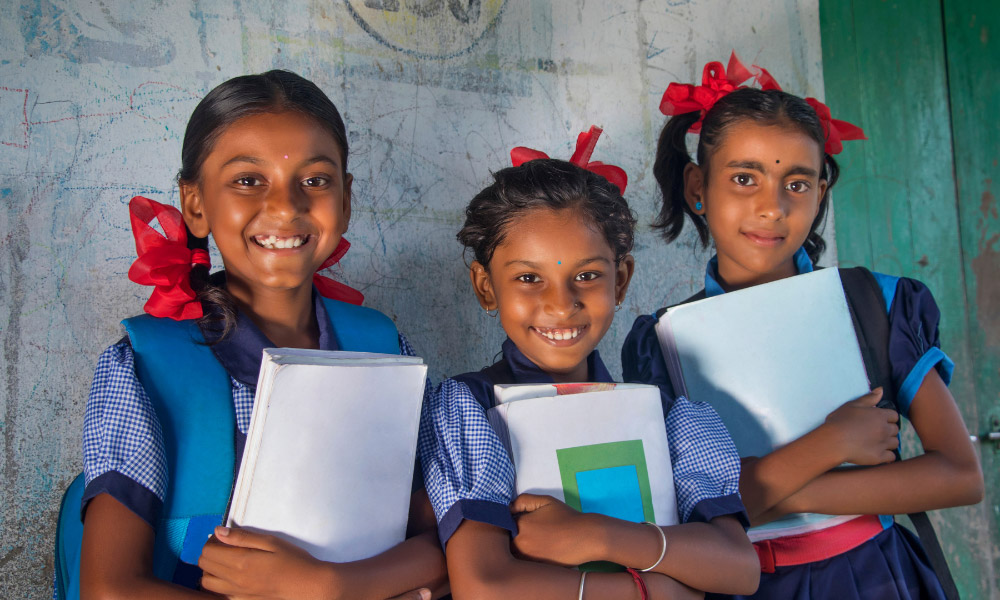

Continue readingA Window of Opportunity Not to be Missed: Investing in Adolescent Girls

Adolescent girls and young women stand to gain the most from a stronger focus on the first 8,000 days of life. However, in many cultures around the world, women and girls often eat last and eat least, affecting both their short and long-term health.

Continue readingBuilding the evidence: Early nutrition sets the stage; subsequent investment plays out across childhood

The first 1,000 days of a child’s life—from conception to their second birthday—are a critical period for nutrition. During this window, appropriate nourishment lays the foundation for physical growth and development, neuro-cognitive development, and overall health.

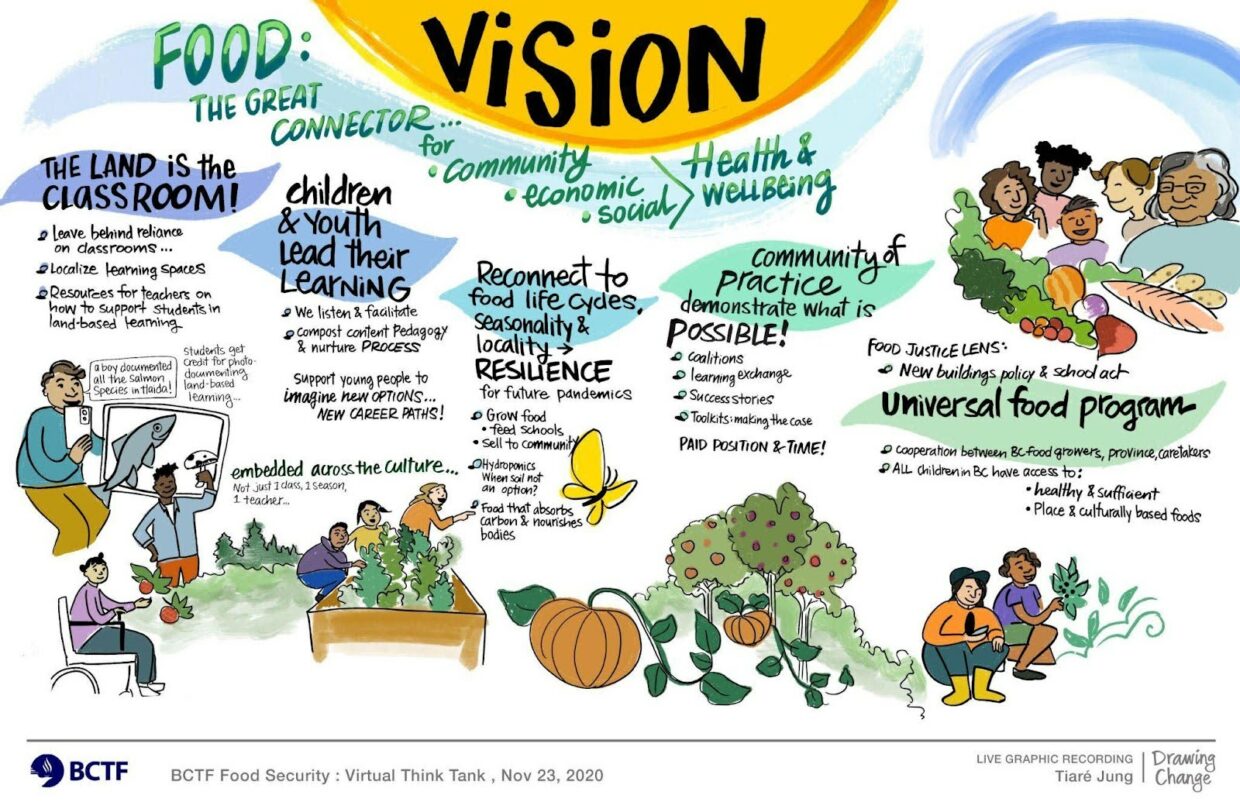

Continue readingShokuiku – How Japan Leverages School Meals as a ‘Living Textbook’ for Lifelong Healthy Eating

In Japan, school meals go beyond just a meal and serve as a “living textbook” to prepare children with the good judgment required for lifelong good nutrition and sustainable diets.

Continue readingThe 2024 Global Child Nutrition Forum – Why Japan?

The 2024 Global Child Nutrition Forum will beheld in Osaka, Japan in December 2024. Japan was selected as the location of the 24th edition of this event because it stands out for providing a nationally owned and managed high quality school meal program.

Continue reading