The 24

th edition of the Global Child Nutrition Forum – the world’s largest and longest

running Forum dedicated to supporting governments and their partners in implementing

high quality school meal programs – took place from 9-12 December in Osaka, Japan

Seeing the Value of School Food Workers and Their Labor

Seeing the Value of School Food Workers and Their Labor

Blog by Jennifer E. Gaddis, Associate Professor of Civil Society and Community Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and Sarah A. Robert, comparative and international education and gender policy expert and an Associate Professor in the Graduate School of Education at the University at Buffalo (SUNY)

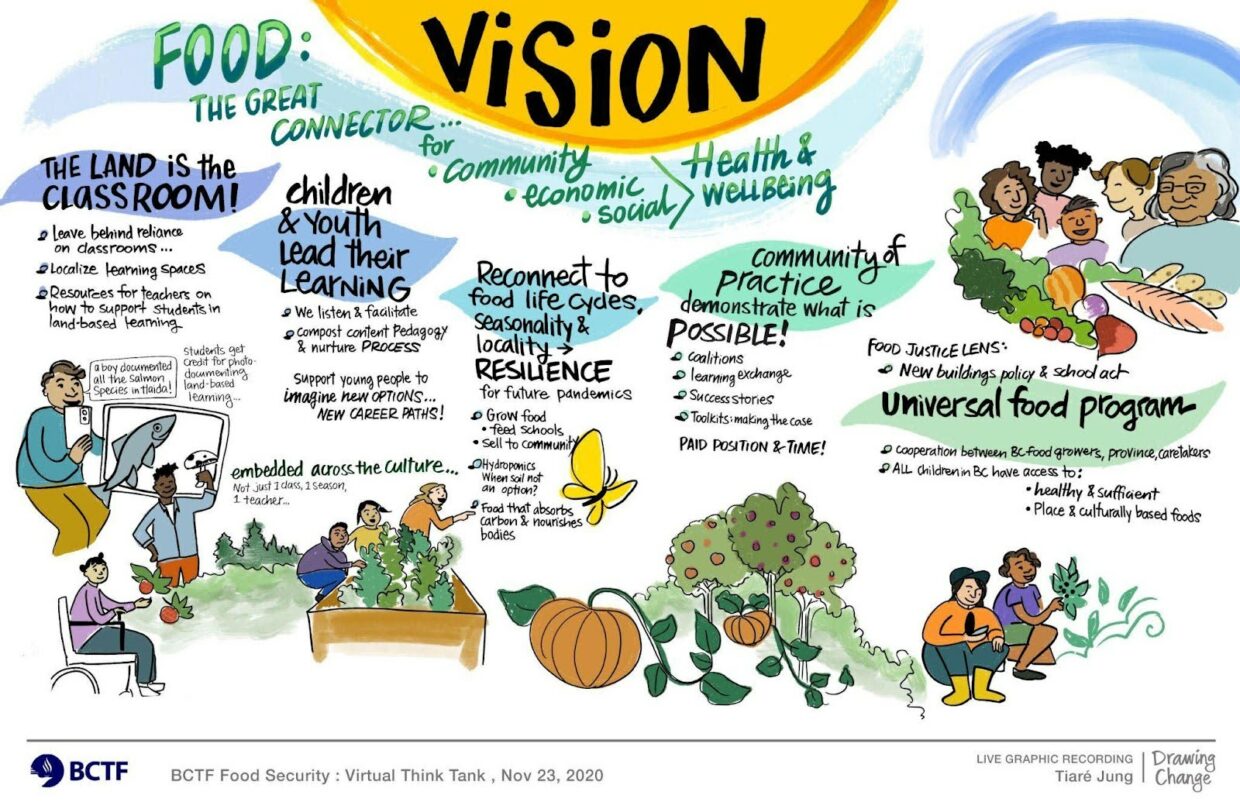

State-sponsored school meal programs not only improve children’s health and well-being, but also promote educational access by helping to attract and keep the most vulnerable populations in school. These programs can also play a vital role in catalyzing broader food system transformations that increase local agro-biodiversity, strengthen food sovereignty, and shift power away from multinational corporations to the communities where children are fed. All of this depends, however, on the paid and unpaid labor of a predominantly female workforce that is too often overlooked in policy discussions, research, and data sharing about school meals around the world.

As the 2024 Global Child Nutrition Summit nears, we encourage participants and other school food stakeholders to “see” this labor and have intentional conversations about the importance of school food workers in an era of food systems transformation. Drawing from our new open-access book Transforming School Food Politics around the World (MIT Press 2024), and global survey data collected by the Global Child Nutrition Foundation, we offer a brief snapshot of gendered labor in school food programs, highlight both the visible and invisible nature of this labor, and suggest an agenda for future data collection and collaborative learning.

Gendered Labor in School Food Programs around the World

Women disproportionately undertake the labor of feeding children at school, reflecting broader societal norms around gender and care work. According to the 2021 Global Survey of School Meal Program database, 82% of programs globally reported that at least three quarters of cooks and caterers are women (GCNF 2022). This database covers 139 countries–roughly 81% of the world’s population–however, only 62% of these countries (86 countries) provided an estimate of the number of people employed in their school meal programs.

So what do we currently know? The 86 countries that provided employment estimates report a total of 3.7 million paid personnel, most of whom worked as cooks/food preparers, and servers. We also know that about 37% of school meal programs in the database emphasize creating jobs or income-generating opportunities for women, resulting in roughly 1,668 jobs created for every 100,000 children fed (WFP 2022). This explicit emphasis on creating jobs or income-generation opportunities for women is more common within low-income and middle-income countries’ school meal programs.

“Seeing” Visible and Invisible Labor

One thing the data doesn’t tell us much about is the contributions of school food workers beyond the core task of feeding children. Yet, as we argue in Transforming School Food Politics around the World, there are both visible and invisible forms of labor that these workers perform. The most visible aspects of their labor involve culinary work (preparing the food children eat), service work, and the maintenance of physical spaces like kitchens and cafeterias. This work may also include menu planning, attending to children’s dietary needs or restrictions, soliciting payment for meals, or verifying eligibility for free meals. The invisible labor, which is rarely (if ever) detailed in job descriptions, but nevertheless expected of many school food workers around the world largely involves what we refer to as “care work.” This includes direct care of students’ physical, emotional, and social needs (e.g., fostering social connections), as well as the care for the natural environment, and the welfare of workers across the school food chain who can be supported through values-aligned purchasing.

For example, in Canada, a country that did not have a national school food policy until June 2024, both the visible and invisible labor of school feeding is performed by paid workers, community volunteers, and adults (mostly mothers) in the home. As one of the contributors to our volume recently wrote, the lack of uniform state-sponsored feeding adds to both the (visible) physical and (invisible) mental labor that women perform in the home. In another chapter, Canadian contributors highlight the invisible labor of teachers (another women-dominated occupation) who use their own time and financial resources to address food security and food justice issues that impact their students.

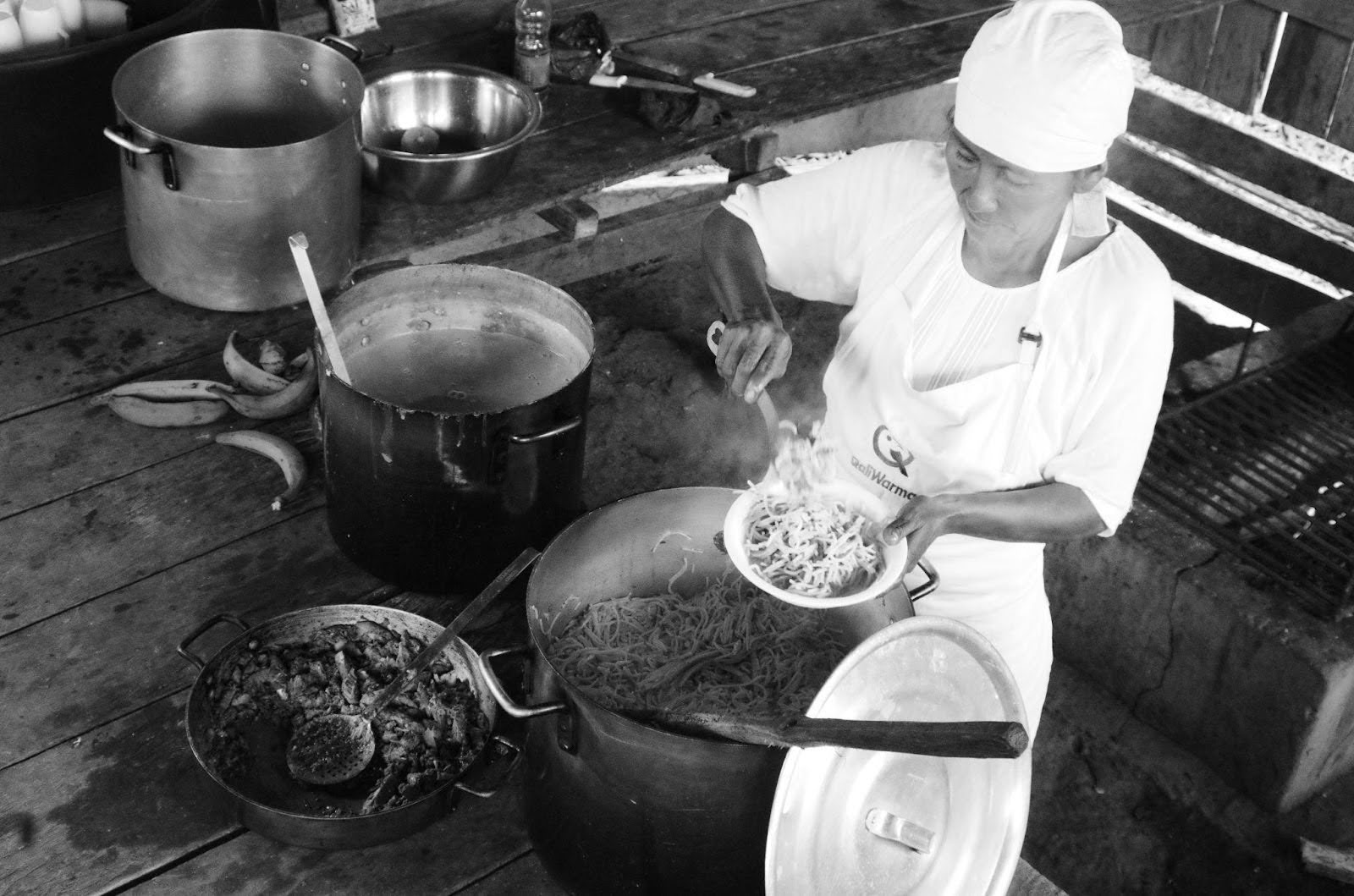

Credit: Emmanuelle Ricaud Oneto.

Other chapter contributors highlight the (gendered) visible and invisible labor in their school meal programs. In two Native communities in the Peruvian Amazon, local mothers take turns preparing meals using ingredients distributed through Peru’s national program and, at times, incorporate local fish or produce that students contribute. Their labor to produce school meals is unpaid, yet vital to the health and well-being of children and youth in their communities.

We know from the GCNF’s data that this type of unpaid labor is not an isolated instance. 32% of programs globally reported in the 2021 survey that less than half of their cooks/caterers received payment for their work. Yet two chapters focused on the Brazilian states of Ceará and Paraná show us that women as agroecologists, as farmers, and as land owners become visible, empowered when procurement contracts prioritize their knowledge and contributions to school meals.

Research and Co-learning about Labor in School Food Programs

As school meal programs grow and change, we see an important role for the 2024 GCNF Forum and the United Nations-backed School Meals Coalition to share best practices, experiences, information, and technical support for creating high quality employment, which recognizes the value of both visible and invisible labor in school food programs around the world.

So how might we do this? In the United States, for example, the federal government recently allocated $1.5 million to fund a 3-year study of its school food workforce. We are eager to learn about similar efforts and hope to connect with other researchers interested in this topic. Robust data collection on the school food workforce within other country-specific contexts would help policymakers and practitioners better understand the current status of the global school food workforce and identify the most promising strategies for “gender-just transitions” within the broader context of food systems transformation (UN Women 2024, p. 91). We encourage other countries to fund research on the school food workforce and also see tremendous potential for organizations like the World Food Programme (WFP) and the GCNF that already conduct global surveys to include more detailed questions about the demographics, work structures and conditions, and impacts of school food workers. We also encourage thematic sessions focused on school food labor at global gatherings of school food stakeholders and the creation of a specific topical area “labor and workforce” in online platforms and databases that aggregate statistics and other research on school food programs.

About the authors:

Jennifer Gaddis is an associate professor of Civil Society and Community Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. She is an expert on school food politics and systems change. Dr. Gaddis is author of the award-winning book The Labor of Lunch: Why We Need Real Food and Real Jobs in American Public Schools (University of California Press, 2019) and principal investigator of a $1.5 million USDA-funded study of the school food workforce. She is the co-editor with Sarah A. Robert of Transforming School Food Politics Around the World. Gaddis is an advisory board member of the National Farm to School Network and has written op-eds on school food politics for popular media outlets such as the New York Times, Washington Post, USA Today, and The Guardian.

Sarah A. Robert is a comparative and international education and gender policy expert and an associate professor in the Graduate School of Education at the University at Buffalo (SUNY). She is the author of Neoliberal Education Reform: Gendered Notions in Global and Local Contexts (Routledge, 2017), awarded the Critics’ Choice Book Award from the American Educational Studies Association. Robert co-edited with Jennifer E. Gaddis Transforming School Food Politics Around the World (MIT Press, 2024). She also edited “Intersectionality and education work during COVID-19 transitions” for Gender, Work, and Organizations (2023); Neoliberalism, Gender, and Education Reform (Routledge, 2018); and the award winning, School Food Politics (P. Lang, 2011).

References

Global Child Nutrition Foundation (GCNF). 2022. School meal programs around the world: results from the 2021 global survey of school meal programs ©. Accessed at survey.gcnf.org/2021-global-survey

Gaddis, J. E., & Robert, S. A., Eds. (2024). Transforming school food politics around the world. MIT Press.

Staab, S., Williams, L., Tabbush, C., & Turquet, L. 2024. Leveraging school feeding programmes for gender-just transitions. In “Harnessing social protection for gender equality, resilience and transformation,” Box 3.4, p. 91. World Survey on the Role of Women in Development. New York: UN-Women.

World Food Programme (WFP). 2022. State of School Feeding Worldwide.

Climate-Smart School Meal Programs

Climate-Smart School Meal Programs

by Melissa Pradhan, Survey Associate: Asia, The Pacific, & The Middle East

The IPCC Reports have repeatedly called for alarms to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in order to limit the increase of global average temperature to 2ºC, if not 1.5ºC. World class evidence and studies have indicated that failing to meet this target will result in catastrophic events with the potential to cause adverse cascading impacts on human life and the economy.

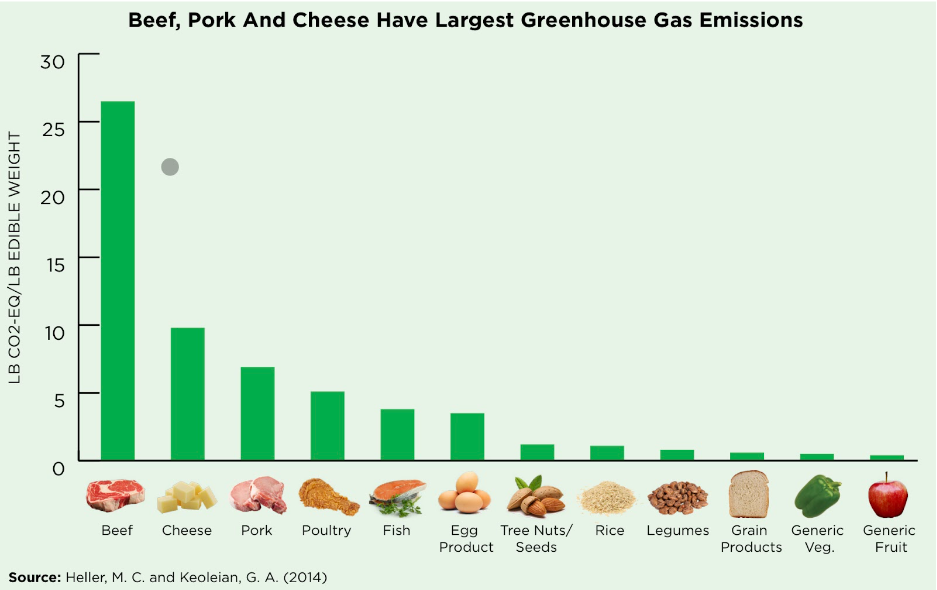

Emissions sourced from the Agriculture, Forest and Other Land Use sector alone have been noted to be just under a quarter of the total anthropogenic GHG emissions making up to approximately 10–12 Gigatonne of CO2eq per year (Smith, 2014). Mitigating GHG emissions from this sector, therefore, has the potential to deliver large-scale emission reduction.

In the 2020 academic year, 330.3 million students received school meal programs globally (GCNF, 2022). In the United States alone, the National School Lunch Program (NSLP) reaches millions of children every day. Nutrition Standards for the US NSLP shapes a USD 14 billion market and food service directors are obligated to adhere to the recommended nutrition standards. However, it was found that the current menus are not aligned with the latest nutritional science, and in addition have huge impacts on the environment. Researchers found that the NSLP menus incorporate the most carbon-intensive foods compared to the diet recommendations from the EAT-Lancet Commission’s healthy reference diet (Poole, 2020).

A study by Stern identified that the use of animal products in school lunches, mainly beef and dairy, was primarily the major driver of emissions (Stern, 2022). This is because beef hot dogs generate seven times more carbon than tofu and veggie stir-fry rice, for example. If all School districts opted for a reduced animal food menu, the US alone could minimize their carbon footprint by 700 million kg CO2eq that is equivalent to installing 99,000 residential solar panels or eliminating 150,000 cars from the roads for a year (Hamerschlag, 2017). In addition, reducing institutional purchase of factory-farmed meat can also strengthen local food systems.

Increasing evidence suggests that school meal programs can be made both healthier and climate-friendly at a low cost without having to compromise on meeting the recommended nutrition standards (Hamerschlag, 2017). As school districts have the liberty to design their own menu to meet the federal nutrition requirements, they hold the potential to influence dietary behaviors and the country’s agricultural landscape for years to come.

The Oakland Unified School District, for example, has already successfully implemented two initiatives – Oakland’s Lean and Green Wednesday Program, and California Thursdays through which they were able to successfully decrease their carbon footprint by 14% simply by reducing the frequency of meat, poultry and cheese in school lunches and opting for plant-based nutritious meals. The district also saved USD 42,000 by cutting costs by one percent per meal (Hamerschlag, 2017). In a similar manner, preliminary calculations suggest that the NSLP could also cut their cost from USD 3.81 per meal to nearly half if the EAT diet is incorporated into their menus.

Outside the United States, as a part of the National Climate Initiative, the German Federal Ministry for the Environment (BMU) has formed a joint project initiated and managed by the Institute for Future Studies and Technology Assessment (IZT) called Climate Efficient School Canteens (KEEKS). Through the project, 22 different ways to reduce GHGs have been analyzed and quantified through the “Measure-Map”. For example, the kitchen staff, chef and caterers are trained to prepare low-cost, healthy, sustainable meals, and utilize energy-saving appliances, plant-based ingredients and low-carbon meat alternatives. This way, KEEKS has significantly contributed to meet the German Government’s target of reducing 40% of the country’s GHG emissions by 2020 by training over 12,500 kitchen staff, reaching 23,000 students across Germany, and offering 140,000 students plant-based school lunches for a week.

Overall, to make school lunches more climate-friendly, some low-hanging fruits could be:

- Incorporating lunches that include more whole grains, seafood, nuts and seeds to meet the protein requirements.

- Reducing the frequency of serving beef and dairy and instead utilizing cheaper forms of protein such as legumes

- Switching to plant-centric meals and/or seafood

- Opting for energy-efficient kitchen appliances and behavior

In addition, local governments and nonprofits can also assist schools in building capacity to begin serving more sustainable lunches. The current policy requirements for school meals should also be updated to allow a wider variety of available climate-smart grain options. As more agricultural products are increasingly susceptible to the changing climate, expanding the options of food items on school menus can also ensure that we are climate-resilient and increase food security.

The world food system is not only driving climate change but also aiding increasing levels of diet-related diseases. It is imperative that we take initiatives to adopt sustainable diets and reduce carbon emissions wherever possible in order to safeguard human life. There are opportunities to opt for a lower carbon footprint for school meal programs through minor changes in our choices of items on the school menu, and the co-benefits in the form of reduced costs and increased nutrients in climate-friendly school meals can help us develop healthier lunches.

References

Global Child Nutrition Foundation (2022). School Meal Programs Around the World: Results from the 2021 Global Survey of School Meal Programs ©. Accessed at link.

Hamerschlag, K. & Polk, U.K., (2017). Shrinking the Carbon and Water Footprint of School Food: A Recipe for Combating Climate Change. Friends of the Earth. Accessed at link.

Poole, M.K., Musicus, A.A. & Kenney, E.L. (2020). Alignment of US School Lunches with the EAT-Lancet Healthy Reference Diet’s Standards for Planetary Health. Health Affairs V.39 N.12. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.01102

Smith, P. et. al. (2014). Agriculture, Forestry and Other Land Use (AFOLU). In: Climate Change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA. Accessed at link.

Stern, A.L., Blackstone, N.T., Economos, C.D. et al. (2022). Less animal protein and more whole grain in US school lunches could greatly reduce environmental impacts. Nature: Commun Earth Environ 3, 138 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-022-00452-3

UNFCCC (2018). Climate-Efficient School Kitchens and Plant-Powered Pupils Germany. Accessed at link.